Reposted with permission from Erster Stories.

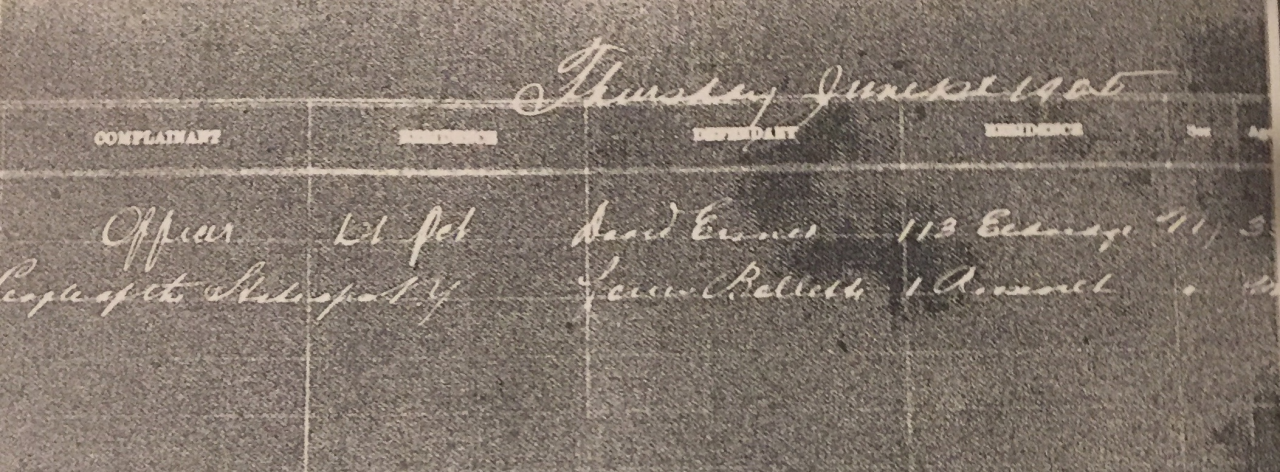

One of my favorite things to explore is criminal law. This comes from years of watching Castle and other crime shows that make solving crimes and pinning sentences to criminals really fascinating. And it turns out that I’ve been able to apply it here as well! This has to do with a telegram from the 24th of July that the business manager of the World, Don Seitz, wrote to Pulitzer regarding the strike. The note’s in code, but decoded (using pages from Pulitzer’s codebook) it reads something like this:

“Situation serious but improving. Morning Journal firm, will not cut [price]. Dealers beginning to take Evening World again. 344 special men put out today. Damage to circulation $80,000. Much rioting. Police have taken up matter actively. Carvalho has persuaded William Randolph Hearst to end Morning Journal’s policy of incitement.”

I was very curious about this “policy of incitement” thing. Often when I dig into criminal law, it begins with a simple question: is ________ illegal? Often, it feels like it should be, but the law can surprise you with the things it allows, especially this far back in history.

In order to answer the question, “is incitement illegal?” I had to know what incitement was. As I’ve learned through being a child of the Internet, when you need a definition, a quick Google search is generally a good place to start. Definitions are even more useful because sometimes terminology changes across different legal codes or gets oddly specific, so having a general sense of what an incitement charge entails helps when finding a charge in the penal code that fits the bill. According to the Internet, “Incitement is the encouragement of another person to commit a crime.” Upon further inspection, this is indeed illegal in a modern U.S. court of law, although specifics vary depending on your jurisdiction.

Now that we know it’s illegal, it’s time to turn to the New York Penal Code. This is where I began to run into issues. Like I said before, the penal code gets oddly specific since the sentences vary depending on what it is the criminal did. In this case, while there is no direct charge for incitement, there is one for inciting to riot. This is part of Article 240, Offenses against Public Order, which contains everything from loitering to criminal anarchy.

Here, we encounter one issue: the memo doesn’t exactly tell us what Hearst was inciting people to do. Although he was engaging in incitement, and there’s a possibility based on the other contents of the telegram that he was inciting to riot, we can’t exactly prove that. But it is possible to pin him to a charge of conspiracy in the fifth degree. The key phrase here is that he works to “cause the performance of such conduct” (that conduct being illegal conduct). So it’s not necessary for him to perform it himself, and this definition is more general so we don’t need to know what he incited people to do.

So we got him, Hearst is a piece of trash who broke the law and should’ve been jailed for up to a year for conspiracy, right? Wrong. I did some more digging, as when I was looking at that definition of incitement article, I found some references to a case in 1969 that caused an update to the current standard for incitement being illegal, which is known as the imminent lawless action test. This was indeed established during the Brandenburg v. Ohio case in 1969, and essentially states the following:

“Advocacy of force or criminal activity does not receive First Amendment protections if (1) the advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action, and (2) is likely to incite or produce such action.”

The imminent lawless action article presents another case that Brandenburg v. Ohio expanded upon: Schenck v. United States in 1919. This case brings up an important discussion that directly involves incitement but calls the general principle of a conspiracy charge into question as well. the main thing this case covered was the difference between free speech as protected in the First Amendment and incitement. America prides itself on allowing people to say whatever they want, and this is actually the first instance I could find of the Supreme Court tackling a limit on free speech like this.

Schenck v. United States is the first discussion we see of incitement being made illegal, even in a weaker definition than we have today. The same sorts of arguments against incitement being illegal can be used against conspiracy as well, especially because a prosecution for conspiracy doesn’t need to prove that they actually took the action, caused the action to occur, or that an agreement even occurred with written acknowledgment. And the first time I can find them trying to tackle this on a federal level is twenty whole years after the strike was over.

So, while Hearst may have been a rat and incited children to riot, in the context of the time we can’t prosecute him for it, as no one even thought to start getting people in trouble for it for another twenty years. However, I thought this was a fun jump down a rabbit hole into criminal law! And don’t worry, I have plenty of other criminal charges I can pin on other people at the World (looking at you, Seitz), so I’ll definitely talk through those as well. Just remember, the law is constantly developing, and it may not be as straightforward as you think.