Tumblr user explorethecosmosandfallinlove asked:

hi i have no idea if this blog is still active it is very late and i am very tired but i was just wondering what you knew about the lodging houses? how they were laid out, what the conditions were like, if the rooms were separate or like all together or a combination? thanks!

Yes this blog certainly is still active! I know a fair amount about the lodging houses, so here we go!

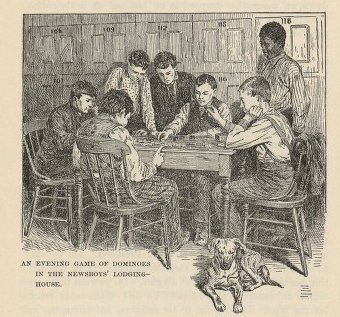

The lodging houses were created to help the homeless youth of New York City after it was discovered that they didn’t trust most of the free programs in the city, thinking the Sunday Schools and the like were just there to trick them and send them to jail. Seeing this, people who wanted to help homeless children decided to create a system that would give the children a bit more freedom while still keeping them off the dangerous streets at night.

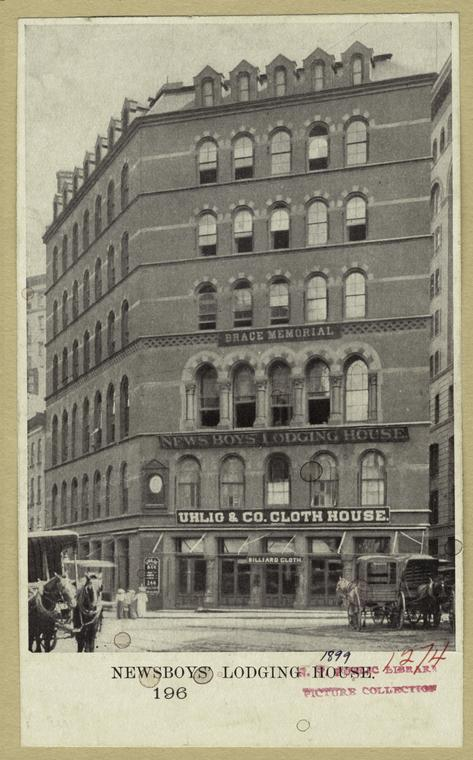

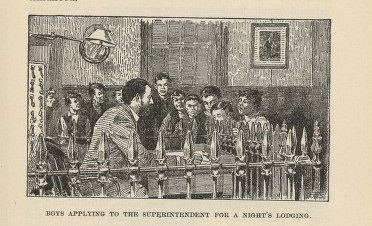

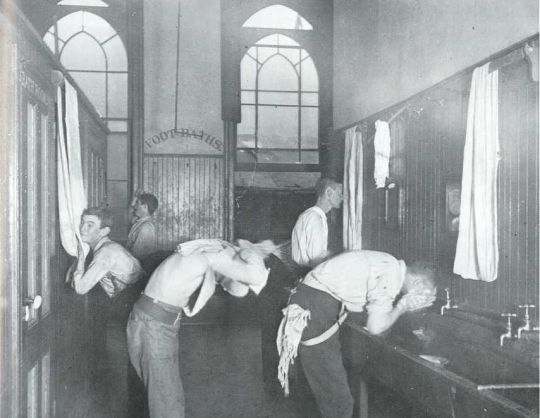

The first of the lodging houses was opened at 9 Duane St. in March 1854, offering a bed and a bath for six cents, and a meal for an additional four. It allowed only boys and also turned away anybody who was found to have living parents. However, children of all races and religions were allowed to stay in the house. Boys were not allowed to smoke or swear in the house, but as long as they followed the rules and kept the midnight curfew they were allowed to come and go as they pleased.

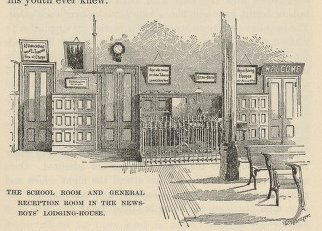

As the house became more established, they also opened a school and required all children staying there to attend either a morning or an evening class. The house was also open during the day as a trade school, teaching not only the residents but also the surrounding community trades such as sewing or cooking.

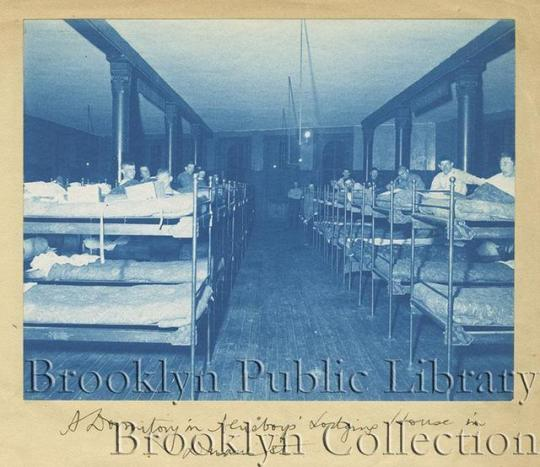

The building at 9 Duane St. had six levels. The first was rented out to shops, the second held the dining room, kitchen and laundry, as well as sleeping quarters for the servants and the superintendent, the third had the school, gymnasium, check-in desk and washrooms, the fourth and fifth floors were the dormitories, and the top floor held a gymnasium. Above that was an attic full of extra beds that could be filled if there was a particularly cold night.

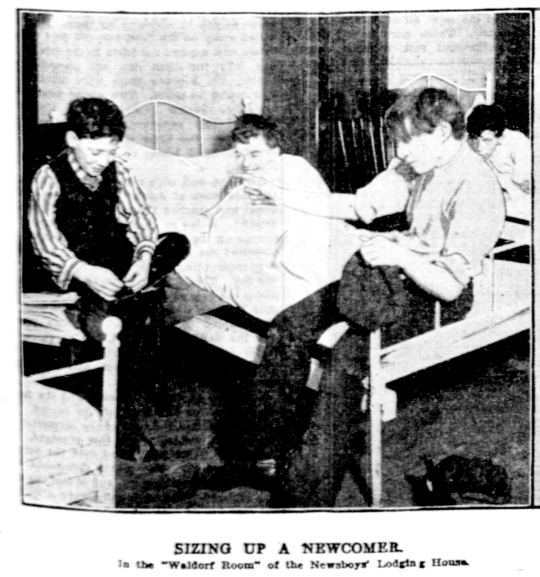

Most boys stayed in the dormitories with rows of bunk beds, but some paid a few extra cents for the opportunity to sleep in a more private bed partitioned from the others by curtains, known as “dude rooms”. In 1904, the Duane St lodging house also opened the “Waldorf Room” which cost 15 cents for the privilege of a room with only five other boys in it. Every bed had a locker assigned to it where boys could safely keep their belongings for the night.

The lodging houses were quite popular. Between their start in 1854 and the publication of Darkness and Daylight in 1892, they claim to have housed 250,000 children. Some of these children remained in the city and were helped to find their own apartments individually or in groups, others were sent to families out West looking for farmhands, some of whom ended up being formally adopted by those families.

The information in this post mainly comes from the book Darkness and Daylight by Helen Campbell. If you want to learn more about the lodging houses, you can check out that book, my “lodging house” tag, or the website “No 9 Duane Street”.

Thank you for the question and if anybody else has anything they want to ask please feel free to do so!