A question from an anonymous Tumblr user:

In the beginning verse of King of New York, some of the newsies list of things they want with their fame. How much did those things cost then?

Response from Tumblr user newsiesquare:

Alright, I’m on it! Gonna go with the musical version primarily, and then whoever isn’t in that who is in the movie (*cough*Spot Conlon*cough*) I will add. Moderate changes I am not adding (like, Davey says “an editor’s desk for the star reporter” in the movie, instead of “a regular beat” because Denton already has a real reporting job, unlike Kath, but the sentiment is the same). All equivalencies made with “today” or “nowadays”, etc. are circa 2017, due to the inflation calculator used.

A pair of new shoes with matching laces: Oh, poor boy, such a small request, don’t think about how his shoe’s are probably too small. Bloomingdale’s would sell canvas lace shoes for Men, Youths, and Boys in their catalog. Ignoring the men’s sizes, youth and boys shoes each sold for either $1.00 or $1.25 a pair, depending, I assume, on the size. Today that would be either $29.89 or $37.32. Now, I’m assuming Bloomingdale’s shoes are more expensive than other places, but still, not that bad.

A permanent box at the Sheepshead races: Okay, there’s a lot of discussion about how this changed from being Race’s line in the movie to Romeo’s in the play and I’d like to talk about that, but somewhere else. For Romeo to do this, that is buy out a box at Sheepshead permanently, it would be pricey. Sheepshead was an elite racetrack, meaning it didn’t exactly sell admission tickets (based off what I can find). However, the Coney Island Jockey Club which opened the track would have membership charges, and annual dues. I can’t find what they charged, but a likely close comparison is the American Jockey Club, also operating with their own track in New York (state). They charged a $75 fee to join and then $25 a year to remain when they opened in 1866. This is equivalent today to paying $1275.16 initially and then $425.05 a year forever, since he want’s it permanently. I know this doesn’t much help for figuring out the costs in 1899, not to mention the added potential losses from gambling, but it let’s us know that this was expensive, so much to the point that it was really only done by the wealthy elite.

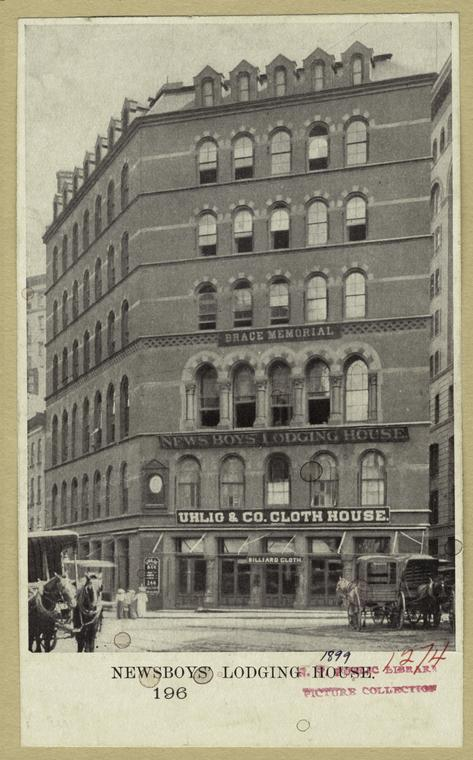

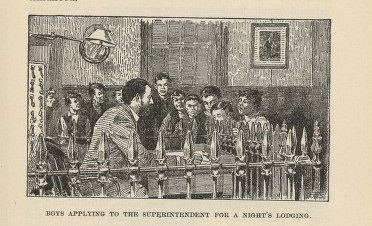

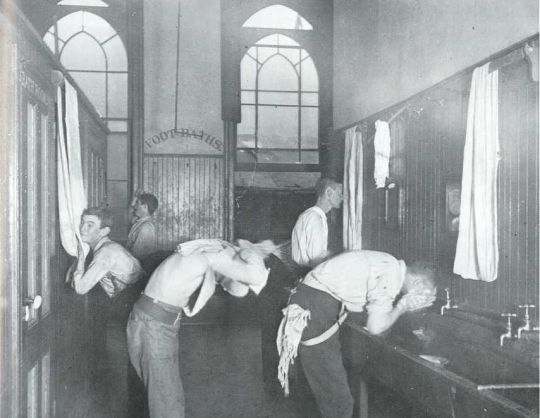

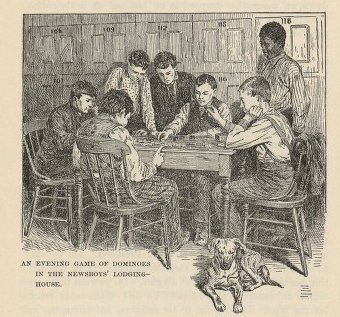

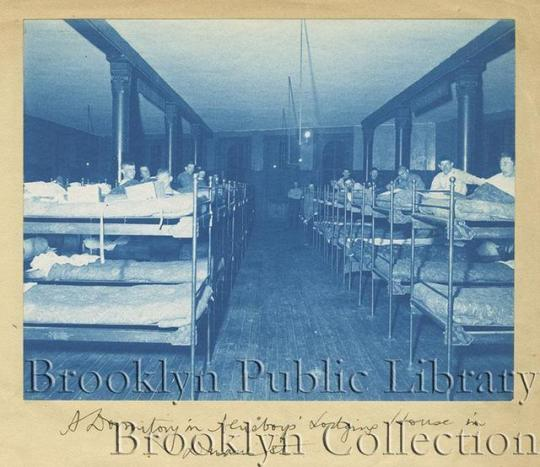

A porcelain tub with boiling water: Um, Spot, why? According to the 9 Duane St website we use, the lodging house had washrooms, as well as hot water. It’s not explicitly stated that the Brooklyn one did, but the DSLH was pretty consistent, so I would assume. So, what Spot’s really looking for is the porcelain tub part. Since he doesn’t have an actual home of his own, he’d probably have to pay for a night in a hotel. He’s really only likely to find something like this in the “good” hotels, i.e., those that didn’t cater to the working class or newly arrived immigrants. A night in one of these could cost between $3.00-$6.00 in 1892 (King’s Handbook of New York City, see Les’ request from the play below), with additional costs for amenities, which I am assuming a tub is not, though I could be wrong. Nowadays, that’s $83.07-$166.13 a night. Not too bad. Also definitely not what those “good” hotels (like the Windsor and the Waldorf-Astoria) are charging now. Les is right, fame is one intoxicating potion, and people will pay so much to feel close to it.

Pastrami on rye with a sour pickle: Henry, you are in a deli. Anyway. Deli’s didn’t use to have printed menus, not that I can find anyway, so I’m working backwards here. I started at Katz’s Delicatessen, opened in 1888 (still there), and regarded as having the best pastrami on rye in New York. I figured if this is all Henry wants he should go for top tier. Their menu lists their “Katz’s Pastrami Hot Sandwich” (also, their sandwiches are apparently huge. Aaaand this is quickly turning into a shameless plug for a deli I’ve never been to. Back to Henry.) for $22.45. Using the cool tool on this inflation calculator, things that cost $22.45 now, would cost (generally) $0.77 in 1899. This seems pretty steep, and was probably closer to $0.40 based off other, non-deli sandwich prices, but also the Katz’s price is high now because it’s a huge tourist destination, and again, the sandwiches are huge.

My personal puss on a wooden nickel: There’s so much to unpack here. Finch? The fuck??? This is partially where my hc that Finch can’t keep hold of money because he buys pointless things comes from. Anyway, what Finch wants to do here is get a customized wooden nickel with his face printed on it. Wooden nickels were novelty coins given by people throwing fairs or by organizations like banks or the Boy Scouts, sometimes they could be traded for drinks. So, Finch could get any old wooden nickel for free, basically. But this boy wants his face printed on that thing. Unfortunately, in my search for how much this would cost, every link in every “general” article was broken. If anyone knows anything about custom printing wooden nickels at the turn of the 20th century, please hit me up, I’m so curious now. However, my assumption is that it wouldn’t have cost much, since we can buy them by the bag for little cost and this company will make you 100 customized wooden nickels for $56.00 (single color and one design printed on both sides). That’s $0.56 per nickel, equivalent in value to $0.2 in 1899 dollars.

A Saturday night with the Mayor’s daughter: Blink??? Um?? Sir?? Pretty sure you can’t buy the Mayor’s daughter. Also pretty sure the Mayor wasn’t pimping out his daughter in the first place, but whatever.

Blowing my dough and going deluxe: There’s no price to this, specifically, just high. Albert wants to live like Rockefeller for a day. I don’t blame him. (Also, just wanted to prove to Maia that I can transcribe what he says in this scene. Because I’ve been told what it is, not because I have any idea how those sounds coming out of his mouth form these words.)

A solid gold watch with a chain to twirl it: Ah, Jojo, you nerd, I love you. While it might have been a reward in his favorite literature, for Jojo, solid gold doesn’t come cheap. The watch itself would cost between $36 and $62.50, according to a “Busiest House in America” mail order catalog from 1897. Keeping with his gold aesthetic, the chain would cost anywhere from $1.46 to $34.00, depending on how fancy he wanted to go. Assuming he goes with a modest but nice looking chain at $12.00, and assuming he doesn’t go insane and buys the $36.00 watch, he’s spent a neat $48.00. Nowadays, that’s $1434.65. Yikes.

A corduroy suit with fitted knickers: Alright, Boots, this is odd, but I can work with it. In the 19th cen. corduroy was largely considered a working class fabric or a “poor man’s velvet”, since it was durable, but soft to touch, and dried quickly, but did not shape well for fashionable use. That being said, corduroy suits do not seem to have been popularized until later (in the 20th cen. when the fabric became “fashionable” again), so he may not be able to get a suit suit, but he could find pants and a jacket easy enough. I can’t find anything for 1899, so I’m using a 1908 Macy’s catalog, as it’s the closest I can find. This catalog has corduroy jackets and pants, sold separately. The jacket only seems to have been sold in men’s sizes, but it cost $4.24 (value of $117.43 today, and $3.93 in 1899). The “fitted knickers” part of his request just means Knickerbocker pants, and the boys’ Knickerbocker pants here sold for $0.76 (value of $21.05 today, and $0.70 in 1899).

My very own bed and an indoor toilet: Damn, Les, you literally want a whole new house, child. Based on the King’s Handbook of New York City from 1892, a “flat” which generally had “five or six small rooms with private hall, bath-room, kitchen-range, freight-elevator for groceries, etc., janitor’s service, gas chandeliers, very fair woodwork and wall-paper and often steam-heat” could go for–*infomercial salesman voice*–as little as $300 a year or $25 a month. Seems like that hits all Les’ requirements, plus some extra amenities. Now, that’s not 1899, but that price in 1892 would be $8306.69 a year or $716.97 a month today. It would be cramped for the family of five, certainly, but it would also be huge step up from tenement living.

A barbershop haircut that costs a quarter: Thank you, Mush, for just telling us how much money you’re willing to spend on “frivolous” things. A quarter. Twenty-five cents. Bless you, this makes my life so much easier. Nowadays, a quarter is equivalent to $7.47. I’m not a guy, so I’ll let y’all decide if Mush is getting a better deal than you or just not getting a fancy haircut…

A mezzanine seat to see the flickers: Movie!Les certainly has humbler goals. From everything I can find, once permanent movie theaters started cropping up, the general admission price at the turn of the century was 10 cents, though I can’t find a specific example for 1899 in NYC. They also don’t differentiate between seats, so this part Les would just have to fight for. A 10 cent movie ticket is equivalent to $2.99 today, but Les can get this just by playing it up for pity buys, as we see in the play.

Havana cigars that cost a quarter: Apparently, this is Snipe Shooter, according to the Genius lyrics for the song. He’s really out here trying to be Racetrack Higgins, though. These, like with Mush’s haircut, evidently cost a quarter, or $7.47 today. Given that they’re Cuban cigars, you know “the good stuff” according to every TV show ever, I’d assume a quarter each.

A regular beat for the star reporter: Job stability? In this economy? Priceless.

Sources (because why not?)

Inflation calculator: https://westegg.com/inflation/

Catalog: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.097392799;view=1up;seq=378;size=175

Prices 19th cen: http://libraryguides.missouri.edu/pricesandwages/1890-1899#merchandise

Movie price: https://www.filmsite.org/pre20sintro2.html

Sheepshead: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09523367.2013.862520?src=recsys&

Les’ brand new house: http://stuffnobodycaresabout.com/2015/12/04/new-york-city-rent-1892/

Katz’s Delicatessen: https://www.katzsdelicatessen.com/

Finch’s nickel: https://coins.thefuntimesguide.com/wooden_nickels/

https://www.thebillfold.com/2015/03/the-history-of-the-wooden-nickel/

Corduroy: https://visforvintage.net/2012/05/03/history-of-corduroy/