Newsboys Try Peaceful Tactics

Who was striking? Manhattan, Brooklyn, Bronx, Staten Island, Long Island City, Mount Vernon, Newark, Troy, Clifton, Tarrytown, Yonkers, Jersey City NJ, Hoboken NJ, Elizabeth NJ, Trenton NJ, Plainfield NJ, Paterson NJ, Fall River MA, New Haven CT, Norwalk CT, Hartford CT, New London CT, Cincinnati OH, Lexington KY

The day after the mass meeting on July 24, the newsboys changed their tactics. They stopped beating and threatening people selling the boycotted papers, turning instead to peaceful discussions in which they tried to make them see their side, or simply to silent glares from across the street. There were a few fights, but they were quickly broken up by the strike leaders.

Despite the removal of threat for people who sell the papers, there are still very few copies of the World and Journal sold that day, because the public was sympathetic to the cause. Even some of the people being given $2 per day by the papers were sympathetic. They would secretly destroy large parts of their papers so they could collect their wages without actually selling the papers.

The papers still said they had no plans to arbitrate, but the boys were unperturbed, saying they would continue the strike for months if necessary. They were confident they couldn’t be ignored much longer. The papers, however, didn’t see it that way. Mr. Carvalho of the World told Kid Blink that his paper couldn’t afford to sell for any less than 60c/100 because their paper is more expensive to produce than the other papers. He told him that the World would go out of business before they would give in to the strikers.

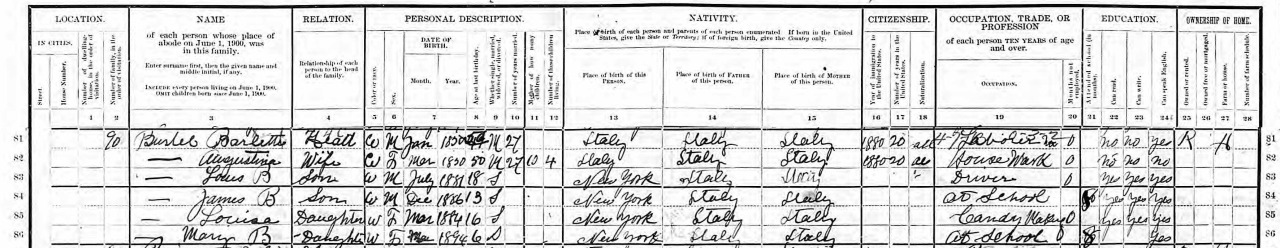

At a meeting in the evening, the Auxiliary Progressive Movement voted to support the strike, and also agreed that newsboys should be more regulated with uniforms, age limits and restricted hours. They propose that boys under 10 shouldn’t be allowed to sell after 9 PM, and that all boys should have parental consent and be required to carry a license and a badge. They believed this would better the newsboys’ quality of life long after the strike was over.

The strike was strong outside New York City as well. In Yonkers, distributors reduced their orders for the papers from 1000 copies to 100, and had trouble selling even that many. In Mount Vernon, they didn’t order any copies at all. The one bundle of papers that did come to town was instantly destroyed by the strikers.

30 newsboys in Lexington KY went on strike because newsdealers make them pay 2.5c for 3c papers and they couldn’t return unsold copies. They tore up the papers not only of those selling on the street but also of people delivering subscriptions. The publishers agreed to their terms and offered to sell to the boys for 1.5c/copy but didn’t offer guarantee of returns. The boys accepted the deal and returned to work the next day.

A parade was planned for the evening, but was cancelled at the last minute because the police didn’t give them a permit.

Sources about this day:

The Evening Telegram: “Newsboys Ready to Show Strength”

The Herald: “Newsboys’ Strike Becomes General”

New York Times: “Newsboys Still Hold Out”

New York Times: “Seek to Help the Newsboys”

New York Tribune: “‘Newsies’ Standing Fast”

New York Tribune: “Yonkers Boys Form A Union”

New York Tribune: “Strikers Ahead in Mount Vernon”

The Sun: “Newsboys Parade To-Night”

The Sun:

“Newsboys Gain A Point”