Reposted with permission from Erster Stories.

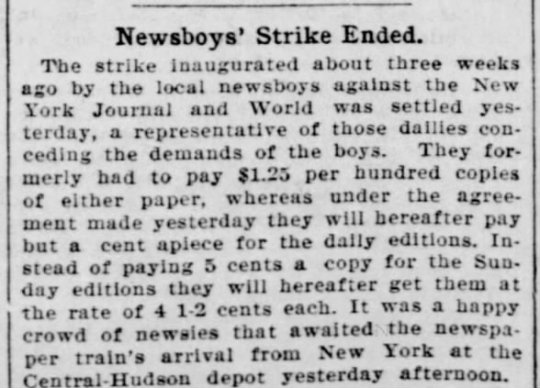

We’re back with more criminal law in the strike era! As promised, I have multiple things that I can talk about when it comes to Don Carlos Seitz and the things he admits to doing in his notes to Pulitzer. I had a lot of fun doing this because I have a hatred for Don Seitz and his inability to function as an ethical human being, so I’m super excited to expose the World’s business manager as the awful person he is.

For this post, I wanna discuss a memo where he openly admits to making threats in an attempt to quash the Sun and other papers that are a part of the “Publisher’s Association” that choose to write about the strike. He specifically mentions approaching one reporter from the Sun, although he also says that he plans to speak with plenty of other papers as well. His language is backhanded and shady, and the way he describes it just feels a bit criminal. He writes, “I preferred to scare them badly and get their cooperation in the end.”

It’s definitely a nasty thing to do, but is that a prosecutable crime? Actually, yes. According to the New York Penal Code, the definition of coercion fits our bill pretty well. When it comes to the penal code, there are always many paths a singular definition can take. One version of coercion in the second degree is defined as follows:

“A person is guilty of coercion in the second degree when he or she compels or induces a person… to abstain from engaging in conduct in which he or she has a legal right to engage… by means of instilling in him or her a fear that, if the demand is not complied with, the actor or another will… Perform any other act which would not in itself materially benefit the actor but which is calculated to harm another person materially with respect to his or her health, safety, business, calling, career, financial condition, reputation or personal relationships.”

Sound familiar? Seitz is essentially threatening the reporters to stop fueling the strike by writing about it, for fear that the newsies will strike against them next. And the newsies striking against these other papers can’t exactly be proven to directly benefit the World, but it would cause material harm to the business and financial condition of the reporters and papers that he’s threatening. That’s either a class A misdemeanor, which could get him anywhere from 15 days to a year in jail, or a class E felony, which is upwards of a year of jail time. According to this correction history record, the main difference between the misdemeanor and the felony is the fear of physical harm or property damage, and that in most cases the first-degree charge is the way to go.

So while that may be illegal in a modern court of law, was it illegal at the time? It’s difficult to confirm, but I found some copies of older penal law books that I think have the answer. According to the 1969 penal law book, the contents of a coercion charge, which is indexed as Article 135.60 (or 135.65 for the same crime in the first degree), appear at the earliest in section 530 of the 1909 copy. The 1906 copy I found has similarly organized sections to 1909, and the numbers go up to 963. So from there, I’m making a safe bet that the first reference to a second-degree coercion charge has already been addressed in penal law at the time of the strike.

So, wow! Unlike with Hearst, we actually can pin him to a crime he could actually be tried for in the era. Unless it wasn’t a crime, of course. As fishy as the description in this letter may sound, and as aggressive a tact as Seitz takes, there’s a possibility that the members of the Publishers’ Association signed an agreement not to slander the other members and Seitz is just aggressively reminding them of said contract. Now, we can’t confirm this one way or the other since we have no record of such a contract, but it’s a possibility I wanted to bring up that would clear the charge.

I know, I know, these criminal law articles are turning out inconclusive so far for one reason or another, but that’s the nature of the law. It’s not always based on what we feel should be wrong. And the one for tomorrow is buried in an even deeper line of questioning than the two we’ve already examined. If we were able to prove it, though, it would be the worst crime we’ve covered yet.